In 1985, Filmation was king of the world. They had successfully done what no previous animation studio had done before and launched a massive 65-episode weekday series directly to syndication. He-Man And The Masters Of The Universe was now the #1 kids show on TV and Filmation was expanding to produce 65 more episodes, a sequel series in She-Ra, and many other projects including re-entry into the theatrical feature business.

Four years later they were dead.

What happened? How did the studio fly so high and crash so hard in such a short period? Most people who know a thing or two about the history of animation will point to the fact that Filmation had two releases in 1987, and both underperformed. But there's actually a bit more to it than that.

Every time I go to a comic convention I see this booth staffed by Andy Mangels where he's selling one book -- Creating The Filmation Generation by Lou Schiemer, which Andy played a hand in making. One year I finally decided to walk over and buy it. Andy offered to sign the book and asked what my "favorite Filmation character" was so he could draw it. I had no idea. I don't think about Filmation that often, to be truthful.

"How about I draw Isis?"

"HEY YEAH! DRAW HER!"

But he didn't feel like drawing Isis so he just drew the Isis symbol.

Oh well. Point is, this is how I acquired the book and the

information in this article.

Reading the whole thing, Schiemer comes off as a pretty earnest fella, if a bit naive. He was a notorious penny pincher and the fruits of his labor reflect that; dozens of animated shows with repeating sequences and reused stock poses. Schiemer swears the reason they look like this is because he refused to send animation production overseas, even though it was the industry standard -- he wanted to keep every job he paid for in the US, even if it cost more and looked worse. That's noble, I guess. But it doesn't excuse the quality of the writing in your average Filmation toon, which was just plain bad.

Getting back to 1985, the peak of Filmation's He-Man high, Schiemer knew it wouldn't last and he had to continue planning for the future. His ideas were to eventually develop an original 65-episode series that was his own idea instead of Mattel's (though there WOULD BE TOYS, of course) and launching a series of 13 planned animated movies called the Filmation Classics Collection.

This collection would consist of a sequel ro Pinocchio, a sequel to Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, a sequel to Sleeping Beauty, a sequel to Cinderella and many others. When had Filmation made movies about those original stories? Never. These were simply sequels to the existing books and fairy tales -- and if someone else happened to, by coincidence, have already made movies based on those books, then that was convenient, wasn't it?

Michael Eisner, who had just taken control of the Walt Disney Company, saw right through this. He prepared to file a lawsuit against Filmation, accusing them of trying to mislead the public into thinking these were Disney films. They were, of course, public domain stories Disney didn't own either -- they just had legal claim to their own versions. Filmation's plan was no doubt capitalizing on the "All cartoons are Disney" belief held by millions of clueless parents...but they technically had the right. They were going to have to prove it in court regardless, though.

Speaking of legal loopholes, Filmation's next TV series after She-Ra was going to be "Ghostbusters," a cartoon based around their 1975 live-action series of the same name and clearly NOT the blockbuster movie that had just come out and was far more familiar with kids. As Scheimer was looking over concept sketches for characters, he stopped at "Tex Hex," a drawing of a ghost cowboy. "Hey, he looks interesting..." Scheimer is said to have stated, "why don't we start developing a different show around that guy?"

Months later, Tex Hex was now the villain of a futuristic space western called Bravestarr, which Filmation pitched to Mattel. They were enthused with the idea, believing cowboy toys were due for a comeback. Their R&D department had been experimenting with infrared tech that could make action figures react when they were "shot" at, which they believed was perfect. Pistol duels, however, were hardly the focus of the in-development show, as its main character could channel the proportionate abilities of animals to make himself as strong as a bear, as fast as a puma, etc. You don't need a gun when you're that awesome. There was no way to translate these abilities into an action figure, so...space duels it was.

Mattel felt so confident in Bravestarr that they put the toys on shelves as soon as they were ready, not when the show was ready. We'll never know if a simultaneous release would have bettered the chances of both products, but a staggered release did not. Despite the nifty infrared technology, cowboy toys were in fact NOT back, and worse yet, sales of He-Man and She-Ra figures were starting to decline. There was far more competition on the rack than there had been just a few years prior, and that was also the case on television...

One thing I find hard to believe is that no one had thought of catering to children on weekday afternoons untul the early 80s. Kids come home from school and they're supposed to do their homework but they don't. They're sick of school at that time of day and want to just sit and relax and watch TV. When He-Man debuted in 1983 it had 100% of that audience -- there was no way it couldn't catch on. But now that everybody knew the secret, Filmation had several competitors, many with better looking animation and better writing. That October, Bravestarr registered as the seventh most watched syndicated kids TV show -- not a disaster, still the top ten, but the lowest opening they'd ever gotten.

In his book, Schiemer pins part of the blame for Bravestarr not catching on with TV stations giving it bad time slots. It was up to the local station where they wanted to put a show, and kids' TV syndication was getting crowded by this point. Even though they startred this whole thing, Filmation was getting drowned out. Every single toy in existence had their own show and now that Disney just entered the ring with DuckTales, things were getting real. I can't speak for anyplace else but my local station, KPTV, was VERY kind to Bravestarr, giving it the most choice slot of all at 4:30 PM. They had DuckTales precede it at 4!

Despite this, I don't think I ever saw it. I certainly don't remember watching it, but at this point in time my TV tastes would have still been for preschool stuff like Sesame Street, Mister Rogers and Pinwheel. Action cartoons were for "big kids." I didn't get to form an opinion on Bravestarr until Qubo (remember Qubo?) started running it at nights. It's....OK, I guess. The animation has a bit more of a bump compared to Filmation's previous material. But compared to something like DuckTales, ho boy, it never stood a chance. It'd be even worse getting to compare them back to back.

While Bravestarr (the show, not the toys) was still profitable, it was kind of a dead end. That put all the hopes for Filmation's 1987 on their Christmas theatrical release, Pinocchio and the Emperor of the Night. Could they turn this year around?

Of course you know the answer to this. Pinocchio is probably Filmation's biggest flop. Lou doesn't spend much time on it in his book before moving on. I have a weird fascination with it because of how utterly forgotten it is (did not know it existed until about ten years ago) and how disturbingly DARK it is (I am glad I never saw it as a kid). It took in around $600,000 on its opening weekend, which was....not great, and ultimately earned a little over $3 million. It enjoyed a small VHS release, but was never broadcast on TV to my knowledge, got no DVD or Blu-Ray, and if it's on streaming anywhere, that'd be news to me.

I checked the archives of my hometown paper, The Oregonian, to see what their reaction was, and found nothing....they completely ignored the movie's existence and there was no review. I assume papers across the country acted similarly. I have assumed for a while this film wasn't properly promoted, but in the years since I've obtained a lot of VHS TV recordings from late 1987 that have ads for Pinocchio and the Emperor of the Night on them. There are several variations, in fact, all with "Coming this Christmas....and that's no lie!" as the tagline. So there was an attempt to get families to show up. They just didn't.

Though it feels unintentional, Schiemer's book reveals just how cheap this film really was. It is mentioned that it went into production in March of 1986, and had its premiere in July of 1987. The animation was done in just one year. Typically, it takes an average of FOUR years for an animated movie to be completed. Also, the budget was publicly reported as about $9.5 million, but Schiemer admits Pinocchio actually cost closer to FOUR million -- he just factored the expenses from the lawsuit with Disney into the final figure.

UPDATE: Someone on the forums uncovered evidence that Schiemer's production timeline for this movie might be a bit inaccurate. Artist Mike Kazaleh said he worked on the movie and that "The Filmation Pinocchio movie was done earlier than '87. I worked on it in '85 and '86, and production was wrapped up by summer of '86." This is around the time Lou claimed it started. If Mike's account is the true one, this movie took longer than a year, but still had a shorter turnaround time.

There are some impressive visual bits in the Pinocchio movie, but overall, it barely looks a cut above where TV animation was at the time. If it looked cheap to you, now you know for sure. But it was probably smart on his end that Schiemer didn't pour even MORE cash into it. He was, however, moving forward with his plans for an animated Snow White sequel called "Snow White And The Seven Dwarfelles."

Screenshot of a rare trailer for the movie's limited re-release, Pinocchio

And The Magic Cauldron

As 1988 dawned, Scheimer wasn't in the best of moods. Pinocchio was a bomb, no one cared about Bravestarr, and worse yet, no one above Filmation cared about Filmation. Some of his last allies had departed the company at Group W and were replaced by strangers. The Westinghouse board now consisted of suits who barely knew what a cartoon studio did or why they had one. When Scheimer would meet with them, their best idea was "uh, why can't you do more He-Man?" Well, Filmation didn't own He-Man, Mattel did, and at that point in time, Mattel had finally decided to make a new He-Man cartoon -- with another studio.

Ever the fighter, Schiemer was itching to battle his way back out of the hole. He proposed a two-hour block on weekends called The Kids Network that consisted of new and repeat material from Filmation's library. The syndication market at this point was so overcrowded I have no idea why Lou thought many stations would spare space for such a thing, but it didn't matter anyway. Group W's decision was to have Filmation produce NOTHING for 1988 and come back in 1989.

Schiemer was aghast. He wanted out. He desired nothing more now than to pull Filmation out from under Westinghouse's thumb, but he lacked the capital to buy it back himself. That's when he gof the news: there WAS a company somewhere interested in purchasing Filmation. Great! Scheimer gave the order to pursue them with zeal. There was just one odd thing about it: the interested party was L'oreal. As in, the cosmetics company from France. What did a makeup manufacturer want with an animation studio?

|

"If you're hesitating for ME to finish the line, you've got a LONG WAIT!" |

|

"And I don't have the guts to say it!" |

|

"Well okay, then here goes!" |

|

"If Filmation was going to be purchased by L'oreal, it must be because...." |

|

"....THEY WERE WORTH IT!" |

|

"OOOOHHHHHHHH!!" |

Schiemer told Group W about L'oreal. They were easily convinced because they wanted to part ways just as badly as he did. And so their representative was sent home to Europe with instructions to start finalizing the deal. A new year, a fresh start. Scheimer vowed Filmation would be bigger than ever in 1989!

....And then he found out what L'oreal actually wanted to do with his studio. It would be months before he discovered this, way too late to stop it, but L'oreal was only interested in acquiring the existing Filmation library, selling that, and using the money to buy other things. If the cosmetics company got them, they would be worse off than they'd be with Westinghouse. They would be shut down; they'd cease to be.

In a panic, Schiemer called up his rich friend, Dino DeLaurentiis, told him about the bad deal he'd been tricked into and asked if he could help. DeLaurentiis flew into a rage as he absorbed the details, and responded with a profanity-laced rant I probably can't repost here. No one was shutting his friend down! He was coming over to the Westinghouse offices with an even bigger offer!

To both their astonishment, Westinghouse wouldn't even meet with DeLaurentiis. All they wanted was to get rid of Filmation and were willing to take the first offer they got, not the best offer they got. They had one, so that was the end of it. That was the end of Filmation.

On the morning of February 8, 1989, three men in black suits arrived at the studio headquarters to tell everyone inside they were fired. Schiemer would not let them in, insisting if their death was inevitable, it at least would not be impersonal. He had to be the one to break the news.

He called all the employees into the auditorium where dailies were screened and told them the whole story I just told you. At this point it wasn't entirely a shock to them that this had happened, except for one man that had just gotten a position a week earlier. "Wait...so you hired me just to fire me?" his voice said from the crowd.

Having done his final duty, Scheimer slunk down the dark hallway of his dying business with head hung low. There was a drawing pinned to the bulletin board of a praying mantis labeled "L'OREAL" devouring its mate labeled "FILMATION."

*****

Was Filmation's death here inevitable? No. Schiemer could have thought of contacting Dino first. He could have never been told about L'oreal. He could have examined that contract a little closer. Even though they were in the hole, they could have survived a while longer, even under Westinghouse, who was willing to let them live even if they didn't know why.

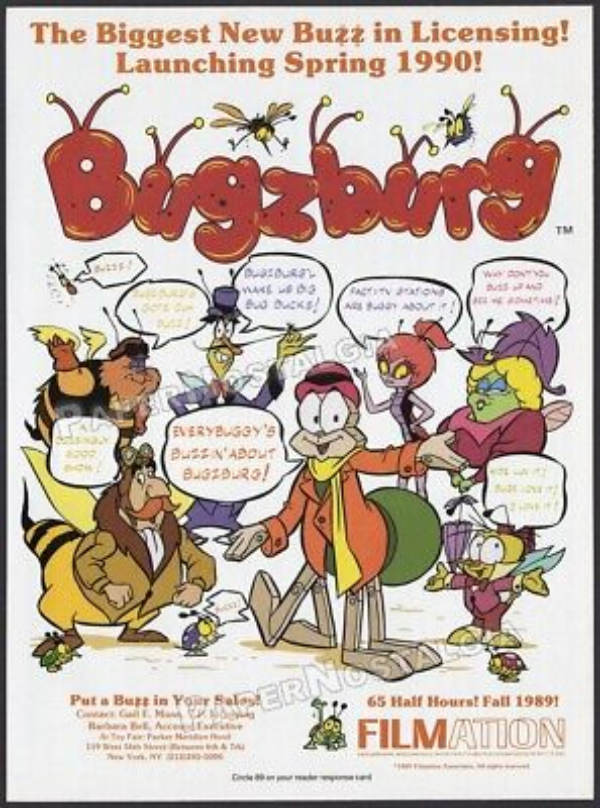

To make up for lost time, Filmation had two 65-episode shows in production for the fall of 1989. They were Bugzburg, featuring characters from the Pinocchio movie, and Bravo!, a spinoff of Bravestarr. One might wonder if a connection to these flops would hinder, more than help, their chances. Well, Filmation simply didn't mention the relation in press materials. "These characters were new to children because nobody saw Pinocchio," Schiemer admitted.

These shows would have absolutely been on the air. At the time of shutdown, Bugzburg had cleared 72 percent of stations in the US, meaning over two-thirds of America had signed on to broadcast the show already. This was seven months before its premiere and Filmation's salespeople would have driven that number even higher, as they had done before. Bravo! had cleared less coverage at that point but probably would have been present on most stations as well. Mind, it was up to those stations to place a timeslot. Bugzburg could've been a 7 AM show while Ninja Turtles and Rescue Rangers enjoyed cushy afternoon slots.

The bigger point is that these syndicated shows were still a reliable source of profit for Filmation. Their brand was recognized and trusted by TV stations. And if they'd kept going in this manner, they could have survived into the 90s, no matter what the quality of the shows was or how popular they were. They had momentum.

At the time Bugzburg and Bravo! were shut down, all 65 scripts had been written, all voices had been recorded and animation was well underway with the first two episodes of each show entirely done. Despite this, not much of either show has gotten out. The pilot for Bravo! somehow made it onto the Bravestarr Volume 1 DVD, but the only surviving clips of Bugzburg are from an animator's demo reel:

Perhaps the most unexpected development here is that the Snow White movie lived. Who knows why, but L'oreal allowed it to be completed under another crew and the picture, now titled Happily Ever After, was screen-ready by 1990. It didn't see release in the US, though, until 1993. Despite everything, it still said "Filmation presents" at the top even though the company itself was defunct.

Since the children's TV syndication market remained viable throughout most of the 90s, I believe a Filmation that didn't sell to L'oreal could have survived that long. What they would've made is the big question. Animation was about to change in a lot of ways, and Filmation's house style and stock system would have looked positvely ancient in comparison. Would they have taken a chance on new art styles and creator-driven concepts? Maybe, maybe not. The last chapter of Lou's book is devoted to all the things he tried to pitch to other studios and failed. Without a studio of his own he couldn't force stuff on the air anymore. His ideas were mostly pre-existing characters (which he had done already) like Tarzan or Flash Gordon, once even a revival of He-Man pitched directly to DEEK about his son, He-Ro.

It's also possible Filmation might have been bought again before syndication collapsed, but not by a random cosmetics conglomerate -- by a major media company, since this is what happened to just about everyone else. Hanna-Barbera became part of Turner Broadcasting, which became part of TimeWarner. The Filmation brand might have lived on to this day as a division of Paramount or Universal. Who knows?

Created by Ares1435 on Deviantart

What we do know is that Lou called the 1989 sale the biggest mistake of his career and he was probably right. Going from riches to rags in just four years is pretty bad. But when you make Pinocchio and the Emperor of the Night and it's the SECOND worst thing you ever did, that's pretty embarrassing.